Life in Apartheid Africa

From the moment white Europeans – the English and Dutch (known as Boers or Afrikaners) colonized South Africa in the seventeenth century, the native black African people were exploited. Africans were treated as inferior beings; among other things their right to own land was taken from them by the white settlers.

In the 1940’s, the Afrikaner National Party invented apartheid as a means to cement their control over the economic and social system. The word apartheid originates from the Afrikaans word for “apartness”. Initially, the aim of the apartheid was to maintain white domination while extending racial separation. Apartheid was part of the system of government of South Africa until the early 1990s, as such, there are many people alive today who have had first hand experience of the repression of this system.

What would life have been like for a black South African under the apartheid regime?

Take a young black boy from a rural village. He would live in the family unit within the village, but typically there would be only women and children in the village. The men would have been ‘given work’ on a farm or mine away from their family and would be required to live away from home.

They may be permitted home once or twice a year to plough their fields. The Africans could not own the land the village was situated on, instead it would be owned by the state and an annual rent would be paid to the government. In early childhood this black boy would help with household chores, then around age five or six, he may be given the task of looking after sheep and calves in the field. While away with the herd, he would practice using his slingshot, forage for wild honey, fruit and edible roots, and catch fish. He would play with other boys when he had free time. If the men were in the village the boys would hear stories of historic battles and warriors, if not, the women would pass on legend and fables with moral lessons entwined.

His knowledge would be acquired through observation rather than direct questions. His life would be moulded by custom, ritual and taboo. He would come across very few white boys while in the village, maybe a traveller or policeman would pass by, but as he got older and ventured away from the village, he would meet whites and have to face the full prejudices of the white people and the apartheid segregation. If he had been fortunate enough to attend school, he would have been given an English name on his first day, which would be the only name he was permitted to use at school. If the school was British, he would be taught British ideas and culture. No part of the curriculum would cover African culture.

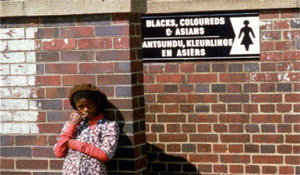

He would only be able to work in black jobs, live in black townships, eat or drink at black establishments, he could use only black hospitals, black public toilets, doctors, and schools. He would have to pay significantly higher rent and taxes than white workers, he would not be permitted to own land or vote in his own country, nor would he be permitted to marry interracially.

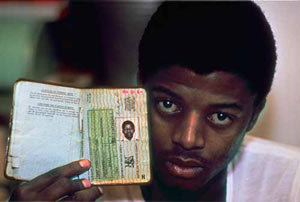

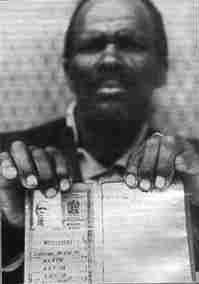

At the age of 16 this black boy would be given a passbook. The passbook included data on the boy’s racial classification (Black, white or coloured), his name, sex, date of birth, residence, photo, marital status, drivers license, place of work or study, and fingerprints. If he obtained work in a “white area” he needed to have his passbook endorsed to allow him access to that area. He must carry the passbook with him at all times. Failure to produce the passbook when challenged, or being in an unauthorised area without the proper endorsement was punishable by detention without trial for months at a time.

If he was unhappy with his treatment and spoke out or joined one of the anti-apartheid groups he was likely to be imprisoned indefinitely as a political prisoner. He may have met white people sympathetic to the oppression suffered by the black people under apartheid, but the majority of the whites, wanted to preserve the status quo and their control over the country.

If this black man lived through the anti-apartheid protests of the 1960s to1980s, the 1990/91 repeal of the apartheid laws, and witnessed Nelson Mandela’s release from prison and subsequent election as President of South Africa, how would he feel? I imagine he’d be outraged at the treatment of the past and optimistic of the future ahead.

What would life have been like for a white South African under the apartheid regime?

Take a young white boy, born say, in Johannesburg to an Afrikaans family. He would have a far more privileged upbringing than his black counterpart. He would have access to the best schools, finest doctors, choicest food and accommodation. He would learn by observation and question his parents, the rightful lowly place of the family’s black servants, and all non-whites.

He would grow up thinking them no more than slaves or pack mules. He would be offended to be in the same room as a black, and would not consider stopping to assist one if he hit it with his car. He would consider it his right to detain anyone who disagreed with the government policy of “apartness”.

If he was a staunch supporter of the apartheid regime, he would be outraged at the anti-apartheid protests of the 1960s and 70s, but arrogant enough not to be too upset when South Africa was expelled from the UN in 1974. By 1990 when President DeKlerk repeals the apartheid laws and frees Nelson Mandela from prison, this Afrikaans man would probably have left the country rather than live by black rule.

Join us soon for another Life Issues.