Life Issues – Greek Theatre

Although it is tempting to accuse William Shakespeare of being the father of modern theatre, the roots of this performance art actually date back much further. Theatre culture was developed in ancient Athens; the forms, techniques, and even terms from ancient Greek theatre have lasted for millenia, and are still alive and kicking.

In contrast to modern theatre’s place as a secular art-form, theatre was born as a religious rite. Back around 1200 BC, in Thrace (in northern Greece), the Cult of Dionysus arose, in worship of Dionysus (aka Bachus).

The Bad Influence

You might recall a jolly drunk man with a crown of leaves and a toga from Fantasia. This is Dionysus, a god of human and agricultural fertility, associated with theatre and wine.

Dionysus helped people to ritualistically release pent-up emotion. In a group setting where it was okay to be ecstatic or hysterical, Dionysians were basically able to express all of their emotions without being accountable. During a celebration of Dionysus, it was okay to scream or yell or cry or laugh, and getting all of these strong emotions out during a ceremony would curb the need to express that emotion later. Basically, the Dionysians were able to purge themselves emotionally, entering an altered mental state, until they were emotionally purified. This act of emotional outcry and purification was known as ecstasis and catharsis (think “ecstatic’ and ‘cathartic’)

The ceremonies were a measured frenzy; chaos with a purpose. The Dionysians practiced ritualistic celebrations that included intoxication, orgies, human and animal sacrifices, and hysterical rampages by women called the maenads. (To get a true insiders telling of the power of Dionysus, try reading the Greek play, The Bachae).

This cult was understandably met with some resistance. Dionysians relished in the opportunity to break with propriety. Their practices were as shocking to Greek culture as they sound today; the point was to transgress social boundaries and get it out of your system. However, over the next six centuries, the cult spread across Greece, growing steadily more mainstream and civilized.

The Birth of Theatre

By 600 BC the Rites of Dionysus were practiced every spring throughout Greece. Now here’s where performance comes into play. An important part of the celebrations of Dionysus was the dithyramb, a choral ode to Dionysus performed by a chorus of 50 men dressed as satyrs (man-goats) and wearing comic phalluses, who played drums, lyres and flutes, and chanted while dancing around an effigy of Dionysus.

Though the dithyramb was originally a purely religious ceremony, like a hymn in a church mass, it began to take on a more theatrical feel, developing into story-telling, drama, and play form.

By 600 BC, Greece culture had moved from a tribal civilization, to quite a modern culture, and was divided into city-states, which were distinct nations developed around major cities or regions. The most prominent city-state was Athens (in Attica), with a population of over 150,000. It was in Athens that theatre took its biggest step.

Until this point in time, Dionysian rites or performances included only a chorus, one solid mass without character. Around 550 BC, a man named Thespis created a startling innovation: he asked an individual to step out of the chorus. This individual was dubbed the protagonist. This was the first actor.

From a modern perspective, this seems like such an obvious ability that the idea of a single actor does not seem very revolutionary at all. But allowing one actor to stand alone allowed him to interact with the chorus. Suddenly the chorus did not have to tell the story; they could show it.

Basically, in a world of songs without plot, Thespis created musical theatre. It would be years before the Greeks would up the number of actors from 1 to 2, and then later from 2 to 3 and then so on. But it was Thespis that opened that door in the first place. It is not without reason that theatre-folk, or thespians are named after Thespis.

In 534 BC, the Dionysian festivals were officially adapted into Drama competitions, which became popular annual events. Thespis, fittingly, was the first winner of such a competition. Government officials would choose the competitors each year, along with the choregos, a wealthy benefactor who would fund the productions in exchange for a tax-break (told you it was a modern culture!)

Building the Theatre

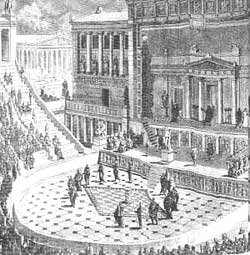

Greek amphitheatres were huge outdoor constructions, with seating in a semi-circle around the orchestra (a small circular performance area, not a musical ensemble). As the individual actor gained prominence, he stepped out of the orchestra, and onto the stage.

Despite the obvious development away from the Dionysian rites, a main goal of the festivals remained true to the original Dionysian purpose; Catharsis. Both the audience and performers were able to purge their emotions during the course of the festivals, even through the group reaction to the events onstage. Despite the fact that the audience of 30,000+ was not overtly expressing the range of emotions for themselves, they were able to vicariously experience the feelings, and thus achieve catharsis.

Greek theatre moved in two diverging directions, the tragedy and the satyr play (as in satyr goat-men, and as in “satire”). Tragedies were intended to teach religious lessons, and often depicted the protagonist who refuses to give in to fate or to society, showing how their faults led to their destruction. Satyr plays were interspersed between the tragedies to create a comic relief

Tragedy

Next in line to Thespis is Aeschylus. He is considered to be the world’s first playwright, and, around 480 BC, he introduced a second actor to interact with the protagonist. This was the antagonist. Aeschylus also introduced props and scenery, and reduced the chorus from 50 to 12. His play, The Persians is the oldest play in existence. His best-known achievement is The Oresteia, a trilogy about the Greek war-hero Agamemnon who was worried by his wife, Clytemnestra.

Sophocles followed suit by introducing a third actor in 468. Although he believed in the gods, he de-emphasized the role of deities in his works, and focused on human drama and the forces of fate. Sophocles’ works are quite well known to this day. It is his plays that are discusted in Aristotles Poetics. Sophocles is the writer of The Oedipus Trilogy (which is referenced in Freud’s theory of the Oedipus Complex).

Much more popular today than he was in his own lifetime is Euripides. Euripides filled his works with social commentary, realism, and cynicism. He placed peasants next to princes, and used his plays to criticize the government and Greek religion. In his time, he was considered a heretic, but he was also the inventor of the prologos (or ‘prologue;’ from logos, or ‘knowledge’) and deus ex machina, a technique through an elaborate machine that would literally descend from the sky and pluck the hero out of a precarious situation.

Comedy

Greek comedy came in two stages: Old Comedy and New Comedy. The best and brightest of Old Comedy was Aristophanes, who made it his business to lampoon all of the untouchables in his culture, including the tragic playwrights, and even the gods. One of Aristophanes’ funniest, most challenging (and saucy) accomplishments was Lysistrata, in which the women overtook the power in their culture and forced their husbands to end a war, by denying the men any physical affection until they gave in.

New Comedy was less focused on society and celebrity figures, and more focused on situational comedy between ordinary people, such as cases of mistaken identity. Menander was the shining start of New Comedy. Unfortunately, very little of his work survives, but parts of his plays were adapted by the Romans, and even William Shakespeare (in A Comedy of Errors) and Stephen Sondheim (in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum).

A Happy Ending?

As Greek culture fell from prominence, so too did Greek theater. By about 400 BC, no new innovations were happening in Greek theatre. Roman culture was growing in prominence, carefully imitating the Greek way, going so far as to copy entire plays. From this time until Elizabethan England nearly two millennia later, very little happened in theatre, beyond maintaining the status quo.

With the Renaissance revival of theatre, neoclassicism brought Greek theatre back to life. Thus it is quite easy to trace a line directly from ancient Greece to modern theatre, and indeed, allusions and adaptations of Greek plays and techniques remain present to this day.

Join us soon for another Life Issues.