Feature – The Sistine Chapel

In the time of Pope Sixtus IV, one of the Vatican’s most widely-loved treasures was commissioned.

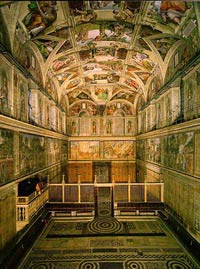

Architectural plans were made by Baccio Pontelli, who designed a chapel which would measure 40.93 metres by 13.41 metres—physically quoting the dimensions of the Temple of Solomon according to its description in the Old Testament of the Bible. It is 20.70 metres high, with a flattened barrel vault roof, and includes small side vaults over six centred windows.

A marble trasenna divides the church into two parts. The smaller section is for the use of laymen Christians. The larger section, with the altar, is reserved for proper religious ceremonies, during which the side walls are covered with a series of tapestries by Rafaello (the painter, not the ninja turtle).

In addition to the work by Rafaello, wall paintings by Perugino, Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, Rosselli. Signorelli, and , oh yeah, a ceiling by Michelangelo (still no ninja turtles) decorate the chapel.

Under the supervision of Giovannino de’ Dolci, the Sistine Chapel was constructed between 1475 and 1483.

The first mass in the Sistine Chapel was held on August 9, 1483, when the church was consecrated and dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary.

Looking Skyward

Originally, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel depicted the heavens as visible to the naked eye—it showed golden stars on a blue sky (recall, if you will, the ceiling at Hogwarts in the Harry Potter series). Michelangelo was commissioned by Pope Julius II della Rovere in 1508.

The actual process of painting the ceiling proved to be quite a feat. (Remember the height of the chapel mentioned above?)

In order to help Michelangelo reach the ceiling, Bramante offered to construct a special scaffolding, which would hang from the ceiling by ropes. Michelangelo, however, was unwilling to embark in any measures that would leave permanent holes in the roof of the chapel. (Was this to preserve the sanctity of the religious space or of his own art? You decide.)

Instead of hanging from the ceiling, Michelangelo himself devised a solution, inventing a wall-mounted scaffolding, using holes in the wall up near the top of the windows.

As he began his painting, the first layer of plaster was too wet, and began to mould. Michelangelo was forced to remove it and start again. In place of this plaster, Michelangelo employed a new mixture, itonaco, which was created by one of his assistants, and is still in use in Italian buildings.

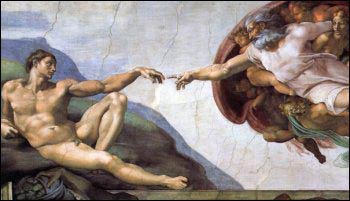

Michelangelo had been commissioned to paint 12 figures: the apostles. Michelangelo surpassed its requirements just slightly, leaving over 3,000 figures when the work was complete. Incidentally, Michelangelo used all male models for his figures, even the women. Female models were rare and expensive, and artists of the era seeking female models were often forced to hire prostitutes.

It took Michelangelo 4 years to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and he completed his initial project on November 1, 1512. Later, he was again commissioned by Pope Paul III Farnese, and painted the Last Judgement over the altar from 1535 to 1541.

Judging the Judgement

The Last Judgement was the object of heavy dispute between Michelangelo and Cardinal Carafa. Michelangelo was accused of being immoral and obscene for portraying naked figures with evident genitals inside the church. A censorship campaign known as the Fig-Leaf Campaign was launched.

This may seem really ridiculous in retrospect, but give it careful consideration. In his own time, Michelangelo was an esteemed painter, but his work was not the indubitable staple of the art community that it has grown to be. When you think about it, it is not surprising that the clergy would become outraged to find a bunch of gentalia on parade above the altar in their most holy temple.

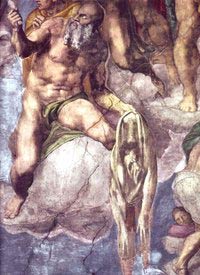

When the Pope’s Master of Ceremonies, Biagio da Cesena, commented that the painting was more suited to a bath-house than a chapel. In retaliation, Michelangelo worked Cesena’s likeness into the piece as Minos, the judge of the underworld. Supposedly, when Cesena complained to the Pope, the Pope responded that his jurisdiction did not extend to Hell, and that the depiction would therefore remain.

The controversy did not die out, and, when Michelangelo died, an order was issued that the genitals be covered. Even after the restoration of the chapel in 1993, this act of censorship remains in place. To see the work as Michelangelo intended it, genitals and all, one can view Marcello Venusti’s faithful copy of the original, which is on display at the Capodimonte Museum in Naples.

Join us soon for another Feature.