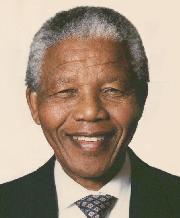

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela

Nelson Mandela is one of the great moral and political leaders of our time: an international hero whose lifelong dedication to the fight against racial oppression in South Africa won him the Nobel Peace Prize and the presidency of his country. Since his release in 1990 from more than a quarter-century of imprisonment, Mandela has been at the centre of the most compelling and inspiring political drama in the world. As president of the African National Congress and head of South Africa’s antiapartheid movement, he was instrumental in moving the nation toward multiracial government and majority rule. He is revered as a vital force in the fight for human rights and racial equality. To many people around the world, Nelson Mandela stands for the triumph of dignity and hope over despair and hatred, of self-discipline and love over persecution and evil.

Nelson Mandela was born Rolihlahla Mandela on the 18 July 1918 in the village of Qunu, near Umtata in the Transkei. The village consisted of no more than a few hundred people who lived in huts. There were no roads, only paths through the grass worn away by barefooted boys and women. The village grew maize, sorghum, beans, and pumpkin. Cattle, sheep, goats, and horses grazed together in common pastures. The land around Qunu was owned by the state, the villagers were tenants paying rent annually to the government. In the area, there were two small primary schools, a general store, and a dipping tank to rid the cattle of ticks and diseases. Qunu was a village of women and children: most of the men spent the greater part of the year working on remote farms or in the mines along the Reef, the great ridge of gold-bearing rock and shale that forms the southern boundary of Johannesburg. The men returned perhaps twice a year, mainly to plough their fields. The hoeing, weeding, and harvesting were left to the women and children. Few if any of the people in the village knew how to read or write. In African culture, the sons and daughters of one’s aunts or uncles are considered brothers and sisters, not cousins. Of his mother’s three huts, one was used for cooking, one for sleeping, and one for storage. His mother cooked on a three-legged iron pot that rested on a grate over a hole in the ground. Everything they ate they grew and made themselves. His mother planted and harvested her own mealies (corn). Rolihlahla was about five when he became a herd-boy, looking after sheep and calves in the fields. When he was seven, friends of his parents observed he was clever and suggested he should go to school. His father cut down a pair of his own trousers and used string as a belt so Nelson would have something to wear.

As was the custom among Africans in those days, his teacher gave him the English name Nelson on his first day of school and said that from thenceforth that was the name he must answer to in school.

His father was an unofficial priest and officiated at local traditional rites concerning planting, harvest, birth, marriage, initiation ceremonies, and funerals. He was also the principal councillor to the Acting Paramount Chief of Thembuland. After his father’s death, the young Rolihlahla became the Paramount Chief’s ward to be groomed to assume high office. Influenced by the cases that came before the Chief’s court, he decided to study law.

After primary education at his local mission school, Nelson went to Healstown for secondary school, then, at age 16, Nelson’s education continued at Fort Hare University College where he enrolled in a Bachelor of Arts degree. He was a fellow student with Oliver Tambo. Nelson was suspended from college for joining a protest boycott, and went to Johannesburg to complete his BA by correspondence. In Johannesburg, Nelson had his first encounter with the conditions of the urban African in a teeming African township: overcrowding, incessant raids for passes, arrests, poverty, the pinpricks and frustrations of the white rule. Nelson gained his arts degree and enrolled for a law degree at the University of the Witwatersrand. He entered politics while studying in Johannesburg by joining the African National Congress in 1942.

When the ANC launched it campaign for the Defiance of Unjust Laws in 1952, Nelson was elected National Volunteer-in-Chief. The Defiance Campaign was conceived as a mass civil disobedience campaign that would snowball from a core of selected volunteers to involve more and more ordinary people, culminating in mass defiance. Nelson travelled the country organising resistance to discriminatory legislation. He was charged and brought to trial for his role in the campaign. The court found he had consistently advised his followers to adopt a peaceful course of action and to avoid all violence, so he was convicted of contravening the Suppression of Communism Act and given a suspended prison sentence. He was also prohibited from attending gatherings and confined to Johannesburg for six months. During this period of restrictions, Mandela wrote the attorneys admission examination and was admitted to the profession.

In 1952 Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo opened the first black legal firm in South Africa, practising as attorneys-at-law in Johannesburg. Through their law firm, Nelson and Oliver were constantly reminded of the humiliation and suffering of the South African black people.

Nelson has a natural air of authority. He is dedicated and fearless. He is the born mass leader.

But early on, he came to understand that State repression was too savage to permit mass meetings and demonstrations through which the people could ventilate their grievances and hope for redress. It was of limited usefulness to head great rallies. The Government did not listen and soon enough the tear gas and the muzzles of the guns were turned against the people. The justice of their cries went unrecognised. The popularity of leaders like Mandela was an invitation to counter-attack by the Government. Speeches, demonstrations, peaceful protests, and political organising became illegal.

Nelson had boxed a little at Fort Hare, but took up the sport in earnest when he lived in Johannesburg. He was drawn to boxing because in the ring, colour, rank, age and wealth were irrelevant. After entering politics, boxing was his training method to keep fit.

During the whole of the fifties, Nelson was the victim of various forms of repression. He was banned, arrested and imprisoned. For much of the latter half of the decade, he was one of the accused in the Treason Trial, at great cost to his legal practice and his political work. After the Sharpville Massacre in 1960, the ANC was outlawed, and Nelson, still on trial, was detained, the trial collapsed in 1961 and Nelson was released. In March 1961, he was a keynote speaker at an All-in African Conference of 1400 delegates in Pietermaritzburg. He challenged the apartheid regime to a national convention, representative of all South Africans to thrash out a new constitution based on democratic principles. Failure to comply, he warned, would compel the majority (blacks) to observe the forthcoming inauguration of the Republic with a mass general strike. In May 1961, South Africa was declared a Nationalist Republic. There was a white referendum, but no African was consulted. Nelson immediately went underground to lead the campaign. The strike was called. The government responded with a large military mobilisation, and the Republic was born in an atmosphere of fear and apprehension.

He left his home, office, his wife and children, to live the life of a political outlaw. His successful evasion of the police earned him the title of the Black Pimpernel. A petition by the Transvaal Law Society to strike Mandela off the roll of attorneys was refused by the Supreme Court.

It was during this time that he, together with other leaders of the ANC constituted a new specialised section of the liberation movement, Umkhonto we Sizwe, as an armed nucleus with a view to preparing for armed struggle. At the Rivonia trial, Mandela explained:

“At the beginning of June 1961, after long and anxious assessment of the South African situation, I and some colleagues came to the conclusion that as violence in this country was inevitable, it would be wrong and unrealistic for African leaders to continue preaching peace and non-violence at a time when the government met our peaceful demands with force. It was only when all else had failed, when all channels of peaceful protest had been barred to us, that the decision was made to embark on violent forms of political struggle, and to form Umkhonto we Sizwe…the Government had left us no other choice.”

In 1961 Umkhonto we Sizwe was formed, with Mandela as its commander-in-chief. In 1962 Mandela left the country unlawfully and travelled abroad for several months. In Ethiopia he addressed the Conference of the Pan African Freedom Movement of East and Central Africa, and was warmly received by senior political leaders in several countries. During this trip Mandela, anticipating an intensification of the armed struggle, began to arrange guerrilla training for members of Umkhonto we Sizwe.

Not long after his return to South Africa Mandela was arrested and charged with illegal exit from the country, and incitement to strike.

Since he considered the prosecution a trial of the aspirations of the African people, Mandela decided to conduct his own defence. He applied for the recusal of the magistrate, on the ground that in such a prosecution a judiciary controlled entirely by whites was an interested party and therefore could not be impartial, and on the ground that he owed no duty to obey the laws of a white parliament, in which he was not represented.

Mandela prefaced this challenge with the affirmation: I detest racialism, because I regard it as a barbaric thing, whether it comes from a black man or a white man.

Mandela was convicted and sentenced to five years imprisonment. While serving his sentence he was charged, in the Rivonia Trial, with sabotage. Mandela’s statements in court during these trials are classics in the history of the resistance to apartheid, and they have been an inspiration to all who have opposed it. His statement from the dock in the Rivonia Trial ends with these words:

“I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment and started his prison years in the notorious Robben Island Prison, a maximum security prison on a small island 7Km off the coast near Cape Town. In April 1984 he was transferred to Pollsmoor Prison in Cape Town and in December 1988 he was moved to Victor Verster Prison near Paarl from where he was eventually released. While in prison, Mandela flatly rejected offers made by his jailers for remission of sentence in exchange for accepting the bantustan policy by recognising the independence of the Transkei and agreeing to settle there. Again in the ‘eighties Mandela rejected an offer of release on condition that he renounce violence. Prisoners cannot enter into contracts. Only free men can negotiate, he said

During his imprisonment at Robben Island prison, Nelson and the other political prisoners were isolated from the general prisoners for two reasons: they were considered risky from a security perspective, but even more dangerous from a political standpoint. The authorities were concerned they might “infect” the other prisoners with their political views.

In the first week the political prisoners began the work that would occupy them for the next few months. Each morning, a load of stones about the size of volleyballs was dumped by the entrance to the courtyard. Using wheelbarrows, they moved the stones to the centre of the yard, and then used either four-pound hammers or fourteen-pound hammers for the larger stones, to crush the stones into gravel. They were divided into four rows and sat cross-legged on the ground. In the afternoon, they were permitted to exercise for half an hour under strict supervision, by walking briskly around the courtyard in single file.

One morning, the authorities placed an enormous bucket in the courtyard and announced that it had to be half full by the end of the week. They all worked hard and succeeded. The following week, the warder in charge announced that they must now fill the bucket three-quarters of the way. The prisoners worked with great diligence and succeeded. The next week they were ordered to fill the bucket to the top. They said nothing and managed to fill the bucket all the way, but the warders had provoked them. In stolen whispers the prisoners resolved on a policy of no quotas. The next week they initiated their first go-slow strike on the island: they would work at less than half the speed they had before to protest the excessive and unfair demands. The guards immediately saw this and threatened them, but to no avail, the go-slow strategy continued for as long as they worked in the courtyard.

Robben Island was without question the harshest, most iron-fisted outpost in the South African penal system. It was a hardship station not only for the prisoners but also for the prison staff.

The warders were white and overwhelmingly Afrikaans speaking, and they demanded a master-servant relationship. The racial divide on Robben Island was absolute: there were no black warders, and no white prisoners.

Part 2 coming soon…