Feature – Escaped Convicts

With so many convicts and so many penal colonies there were bound to be some escapes.

By 1814 in Tasmania there had been so many convicts escape that an amnesty was proclaimed. But by the time the deadline came for the amnesty only a handful of convicts had surrendered and the colonists were frantic.

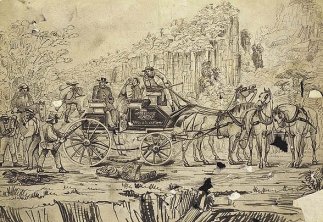

The escapees were “going bush” and living as bushrangers in the Australian outback. They would lead a life of robbery and roam the plains and mountain ranges in search of fortune and adventure. They had no regard for authority and little respect for other peoples property. They would find easy pickings supplying stolen horses, cattle and sheep to the gold diggers while the law tried without success to capture them.

During this time there was a Rebel leader named Michael Howe. He had served in the Yorkshire Army as a soldier. After a few years of training he deserted and was later caught robbing a stage coach on the King’s highway.

In 1812 he was transported to Van Diemen’s Land at the age of 24 and absconded almost immediately. Two years later he and a fellow convict named Whitehead recruited together twenty-eight bushrangers and formed their own convict rebel army. Many of these convicts he had helped to escape.

Michael Howe was a natural leader and had great organisational skills. He would eventually gather almost two percent of the convict population of the island. He invited the “slaves” on the farms he raided to join the rebel army.. Many compared him to the likes of Robin Hood.

He was a trusted man and soon acquired a network of associates among the farms and convicts. They would tell him as soon as any troop movements began.

Howe and his rebels would target landowners who were known to treat slaves badly. An especially hated “flogging magistrate” named Adolarius Humphrey lived some thirty miles from Hobart. Howe struck while he was away, burning his corn, trashing his house and running off hundreds of his merino sheep. The convicts saw this as a huge victory and Howe’s following grew.

His army was so well regimented that they would wage war on the Colonial authorities and military garrisons, gathering recruits as they went.

This carried on for years – it seemed he couldn’t be stopped and his popularity continued to grow.

Eventually his right hand man, Whitehead was recaptured but this didn’t deter him – he continued to recruit and ranged across some 500 square miles.

In 1817 after almost five years on the loose, Michael Howe’s luck began to run out. He had acquired a devoted aboriginal wife, Mary. One day, soldiers ambushed the couple and although Howe was able to escape, his wife who was heavily pregnant was unable to keep up with him. As gunfire exploded, Mary was shot. The army claimed afterward that Howe had shot his own wife in cold blood to stop her talking. Howe insisted it was an accident.

Mary lived and the army told her of her husbands betrayal. She wanted revenge. After recovering from her bullet wounds and giving birth to her baby she volunteered to track down her traitorous husband. But they still could not find him.

Howe now sought a pardon with the new Lieutenant Governor. In an apparent effort to stop the war the Lieutenant offered a conditional pardon for all Howe’s crimes except murder and a strong-recommendation for clemency on the murder charge itself if he would surrender himself and his force.

Howe returned to Hobart and began to plan a normal life leaving his army behind. But the authorities failed to keep their side of the bargain. Howe realised it was a trap and fled back into the bush. He was declared an outlaw again and a price was put on his head.

Howe was now without his army and was just another outlaw on the run – but bounty hunters now wanted the reward for finding him.

Two men tried to capture him while he was asleep one night. But Howe managed to fight them both off and kill them.

In 1818 he barely escaped from another bounty hunter. The hunter had hired an aboriginal tracker from Sydney to track him down.

Eventually in October 1818 his luck really did run out. Three men surprised him while he was resting beneath a tree. They beat him to death on the spot with the butts of their rifles. They cut off his head and carried it back to Hobart where the Lieutenant Governor put it on public view.

Howe could not have survived on the run for five years without the support and sympathy of other convicts and some of the free settlers in the area.

Join us soon for another Feature.